Building a New Britain

Investing in Britain’s Public Realm

The British Disease

Britain’s economic preeminence ended around the year 1870. For most of the period since, we have been haunted by a pervasive sense of decline, particularly when comparing our fortunes to those of international peers. In recent years, that sense of decline has accelerated, becoming not just relative but absolute, with working people’s real wages unchanged in 18 years.

The performance of the UK’s economy since its apogee. Sources: ONS, Long-term productivity database, Bank of England’s Millennium of Macroeconomic Data, Author’s Calculations. Notes: Peers are defined as the average of the US and the modern-day Euro Area.

In a recent report, Labour Together described a global “age of insecurity” that exacerbates many of our economic woes. Thirty years ago, we appeared to have entered an era of order and security. The West had won the Cold War and peace reigned. Globalisation was lifting billions from poverty and delivering cheap goods to our shores. Today, in this new age, those certainties are upended. Rising geopolitical tensions are causing an increasing number of negative economic shocks. All nations have been affected, but Britain has been more affected than most. Our national underperformance in this age of insecurity is singular and striking. This paper explores the cause of that underperformance and what we can do about it.

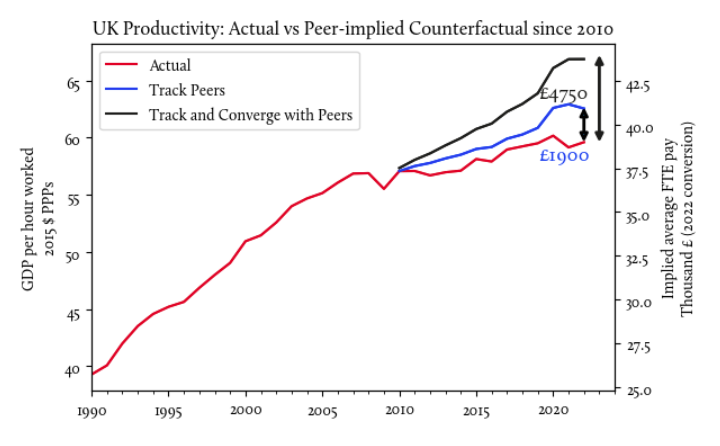

We show that the UK’s economic failure is primarily the result of low productivity. For each hour we work, Britain’s economy creates less than our more productive peers. New Labour Together analysis shows that the UK’s productivity shortfall versus peers increased from around 20% to nearly 25% from 2010 to 2022. This relative decline is notable. Countries that are behind the so-called “frontier” should be able to catch-up to more productive peers, by imitating what makes them so productive. Our analysis shows that if the UK had converged to peers at a typical rate, our productivity would now be 12% higher. As improvements in productivity tend to move directly to increased wages, Britons should be earning nearly £5,000 more each year - far more, it should be noted, than the recent rise in their household bills.

The wage growth that wasn’t. Source: OECD Productivity Database, 2015 PPPs, Author’s Calculations.

A key feature of the UK’s low productivity is its regional composition. Britain’s productivity problem is a regional problem. If every European country was able to boost its regions with lower productivity to the level of its 75th percentile, they would experience some economic growth. Because many of Britain’s regions lag so far behind the best performing, the additional growth would be higher than in any other developed country in the world. This includes, quite remarkably, a country like Germany, whose least productive regions were, until just thirty years ago, occupied by Soviet troops.

London-centric Britain. Source: ARDECO, Author’s Calculations.

The cause of the UK’s uniquely low productivity is low investment. Both public and private investment in Britain have languished at the bottom of the pack for decades. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has shown that between 2009 and 2019, capital levels per worker in the UK fell, reducing productivity. In comparable countries, it increased. If the UK had pursued the increase in capital-per-worker (“capital deepening”) of its peers, it would have roughly matched their productivity growth.

Low UK investment levels. Source: IMF Investment and Capital Stock Database, Author’s Calculations. Note: Advanced Economies are the 31 OECD countries that appear in the IMF’s Investment and Capital Stock Database.

What’s causing low productivity. Source: ONS, BLS and Statistics Canada via ONS. Notes: ONS calculations of contributions of capital deepening, labour composition and MFP to market sector output per hour worked growth.

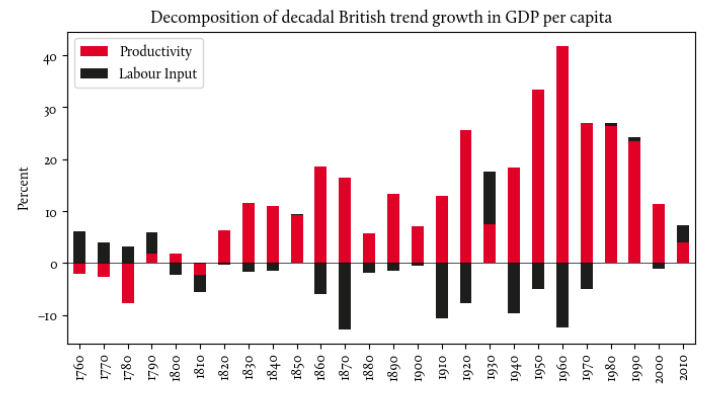

Looking ahead, productivity growth is the only way to deliver sustainable growth - and deliver the highest GDP growth in the G7. After some successes in the 2010s, employment is high. While there is some scope to boost this further, this cannot be the source of exponential growth. Instead, we must help the UK’s workforce produce more while they are at work. In the last decade, we have failed to do this: productivity growth has been at its lowest in any period since the first productivity gains of the Industrial Revolution.

What’s causing low productivity. Source: ONS, BLS and Statistics Canada via ONS. Notes: ONS calculations of contributions of capital deepening, labour composition and MFP to market sector output per hour worked growth.

Delivering growth is the most fundamental of Labour’s missions, underpinning improvement in public services and spreading opportunity. This is partly about the level of growth. High trend growth is associated with lower recession risk, as new analysis set out in this paper shows. It is also about the resilience of growth. Reducing risk protects households from sudden shocks that push up bills, such as those experienced as a result of Britain’s vulnerable energy system. Growth must also be broad-based across the income distribution and regions. The negative impact of high income inequality on relative social mobility is well-known, popularised most famously by Alan Krueger’s “Great Gatsby Curve”. In this paper, we show that high regional inequality has the same impact, and illustrate it through our own “Pip Pirrip Curve”, offering a British literary protagonist for this very British problem.

The Pip Pirrip Curve. Sources: IMF and OECD.

Delivering on the growth mission is also crucial for improving public services. We show that if the UK’s productivity had converged appropriately with peers, we could have had c.15,000 more doctors, over 40,000 more nurses, and around 75,000 more teachers while keeping spending constant as a share of GDP.

Investment Principles

Growth is at the heart of Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves’s agenda and investment is the cornerstone of boosting growth. This paper outlines a set of principles that can guide Labour’s plans to invest in Britain’s public realm:

1. Public investment must be fiscally responsible. The financial crisis created by the Conservative’s budget last Autumn shows that fiscal space in the UK is a concern for financial markets. Failing to account for these concerns will increase the risk of damaging crises and mean higher rates even in good times, further undermining economic security for working people.

2. Public investment should focus on where it can best crowd in private investment. Both public and private investment are much lower in the UK than in comparable advanced economies. But 85% of the shortfall is due to private investment, so public investment cannot make up the shortfall alone. Every pound of public investment should sit alongside proactive measures to crowd in private investment.

3. Investment should build resilience, and in particular, Britain’s energy security. In an age of insecurity, we must reduce the vulnerabilities that come from our reliance on imports, and particularly imported fossil fuels.

4. Investment should focus on regions where investment has historically been lowest. There has been severe regional inequality in how public funds are spent, with transport spending particularly low in the North relative to the South, which have left a lasting imprint on regional inequality in Britain.

5. Investment should focus on areas where it can have the biggest impact on productivity. This will boost aggregate growth, drive wages higher, and increase the funds available for public services.

6. Investment should be seen as one tool among many. In particular, it should be paired with regulation and partnership approaches to maximally crowd in private investment.

Three Acts to Rebuild Britain

Based on these principles, we argue there are three areas for investing in the public realm that Labour could emphasise to the country: energy, housing and infrastructure.

The Energy Independence Act

The UK energy system relies on imported gas. The high pass through from wholesale to retail prices allowed by the Government, and the long-running underperformance of energy efficiency programs, means UK households have been exposed to a much bigger shock than those in the EU. This is a key reason why the UK is expected to have the lowest growth in the G7 in the years to come. In a global age of insecurity, the risks to households from imported energy will continue to be high. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates the fiscal cost of remaining on gas at 13% of GDP by 2050-51. Investing in homegrown energy will build resilience, boost growth and crowd-in private investment.

As outlined by Ed Miliband, an Energy Independence Act could address this fundamental challenge. At the heart of this would be the policies set out under Labour’s plans to invest in Britain’s energy system. Funds that are still unallocated within that policy should be directed with an eye towards which green investments will be most growth-enhancing. Further thought should be given to how best to integrate Labour’s investment plans in our energy system into a wider industrial strategy, and how the UK can become a leader in green innovation.

A British Homes Act

Homebuilding in the UK has been too low and too slow for far too long, with the restrictive planning system the prime culprit. Given the constrained fiscal situation in the UK, housing should be a focus of Labour’s investment programme. Planning reform can unlock private investment and potentially generate revenue for the Treasury. We welcome the Labour Party’s proposal to build a new generation of “new towns”. The last New Towns programme, initiated by the post-war Labour government, still generates around £1 billion a year for the Treasury. It is also beneficial because inadequate housing supply is a key constraint on growth, driving outmigration from high-productivity areas such London among those in their 30s and 40s. Our analysis shows that, after controlling for occupation and qualifications, being in London earns you a nearly 25% wage premium. This implies that keeping people in London could boost their wages by £9,000 and provide £5 billion for the Treasury.

We propose a British Homes Act, which will support the drive for homebuilding that Keir Starmer has argued for. Central to this bill should be extensive reform to the planning system. But it should also include institutional reform. The Government could create a new vehicle, GB Homes, building on the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s proposal for a national master-planner. GB Homes would develop a national strategy for homebuilding and work with regions and local authorities to develop plans and ensure their delivery through greater private investment, while sharing some of the proceeds from land value extraction.

A British Infrastructure Act

Of all possible public investment, infrastructure has among the largest impacts on productivity. It crowds in private investment by increasing the connections between producers and consumers. We can further enhance the impact with other levers, such as planning reform, to make building infrastructure quicker and cheaper. Infrastructure is also an area where there has been particularly high regional inequality in spending. As the Resolution Foundation has shown, inequality in transport spending explains most regional inequality in capital spending.

A British Infrastructure Act would look at the full set of tools at a future Labour government’s disposal. It would start with reforms to the planning system and government management of infrastructure programmes, to provide consistency and longer planning horizons for infrastructure planning. It would prioritise rectifying regional inequalities in infrastructure spending. It would be underpinned by a framework that could assess whether to renew the HS2 link to Manchester, and if not, how best to distribute the funds across the North.

This paper offers an outline of these three Acts. Taken together, they explain how Labour’s ambitious proposals for unlocking investment could transform Britain’s public realm. The case for doing so is now unarguable. For too long, Britain has been held back by low investment, suppressing productivity. This has kept wages low and curtailed growth, starving public services of funding. Labour’s willingness to use the state as a catalytic investor, leading so that private sector investors can follow, is a genuine dividing line between the two major parties at the next election. The Conservatives have shown themselves to be either unwilling or unable to boost investment. The Britain we live in has been governed by that ideology for thirteen years. It is time to build a new Britain.